The COVID-19 virus has radically changed day-to-day life for individuals, businesses, and governments around the world.

The daily question on everyone’s mind is “when do we get back to normal?” Organizations are asking “how do we prepare to get back to normal?”

These should not be the only questions for you as a leader.

Once you have safeguarded lives and stabilized operations, your priority is also to think about future improvement. Your key question should be the opposite of others who are focusing on “normal.” Your question is: “which of the changes we’ve made are worth keeping, and what further improvements can we make?”

This article helps you do that: to “innovate forward” rather than “revert backward.”

This crisis presents opportunities

The current crisis, like any crisis, poses plenty of danger for individuals and organizations.

Yet there is a positive side.

As a leader, you’ve probably wanted to make some major changes in the past. You probably didn’t make those changes for good reasons … at the time. Most CEOs and senior executives are rewarded for stability and predictably meeting quarterly or annual targets.

Major change can deliver positive results but can also be unpredictable and disruptive. Therefore, major change when things are “normal” usually looks too risky and can be far outside comfort zones. It’s usually avoided, but doing so precludes the potentially dramatic future improvements.

Risk has now become reality. Major change is now happening to your organization and its ecosystem, whether you like it or not. Comfort zones have been breached and even obliterated. However, this very change, though unwanted and possibly destructive in some ways, is the very vehicle to help you increase agility and innovation at less risk to you and the organization than before.

Newton’s first law of motion helps us out here (An object that is at rest will stay at rest unless a force acts upon it, and an object that is in motion will not change its velocity unless a force acts upon it). The law generally applies to change as well, as once change is happening, it is easier to keep it going. Jim Collins’ “flywheel effect” (1) also describes well the positive effect of change momentum.

There is one important caveat: in the physical real world rather than the theoretical of Newton’s law, gravity and other drags eventually slow the motion down to a stop. Momentum only carries you so far. So it is also with organizational change. “Organizational gravity” will slow momentum unless you keep it going with consistent support.

Employ the change formula to your advantage

This extract from Wrong Until Right – How to Succeed Despite Relentless Change provides some context about why change is easier now:

The phrase “change is hard” is a common one.

Change is actually easy! People change all the time, as long as the change is to their benefit (so they have the commitment), and they have the ability or competency to make the change.

For example, if you are driving and encounter a problem on the road ahead that has traffic jammed, what will you do? You will probably take an alternate route to might get you to your destination faster than staying stuck in traffic. You don’t need someone “motivating you” to consider or make the change.

People make major decisions and changes such as where to live, job change, etc. every day. They are either not satisfied with the status quo, or else the benefits of change seem better than the status quo. Just because the changes are more difficult does not mean that people don’t make them. Change is really a benefit/cost calculation, even if the calculation is not consciously made.

The calculation – the psychological formula for change – is that the pain of the change must be less than the pain of not making the change. Or, the pain of change must be much less than the future gain from making the change.

The change formula:

|

Pain of change |

< |

Pain of not making change |

|

OR |

||

|

Pain of change |

<< |

Future pain of not making change and/or benefits from making change |

This explains why change is often viewed as “hard.” Maintaining the status quo is easier – less painful if painful at all – rather than making a change. Why would someone leave their comfort zone when the pain of changing is greater than staying in the comfort zone?

Or – why change and endure the pain in exchange for some nebulous future benefit? The future benefit must be much bigger than the pain of change since the pain of change is far more “real.” The pain is now, but something in the future is “out there” and may or may not happen. The risk of betting on future benefits must be overcome by the potential payoff being big enough or real enough.

The real issue is not that change is hard. It is that finding something worth changing for in a group or organizational context is usually hard. Those asked to change did not initiate the change, don’t understand why the change is needed, and don’t see how their gain outweighs their cost or pain of change. That puts change on the wrong side of the equation.

Change due to the COVID-19 crisis happened because the virus made the pain of not making changes greater than the pain of the changes. In short, the virus “unstuck” things. It made major change desirable compared to the consequences of not changing.

For example, remote work was not allowed or was even unthinkable in some organizations prior to COVID-19. It required major changes not only in technology but HR policies, legal agreements, etc. However, the immediate need for remote work instead of shutting down operations amid the crisis overcame – and usually quickly – all the former hurdles perceived as too difficult or even impossible.

Now that organizations are “unstuck” – the flywheel is moving – further change is easier.

Those changes you had wanted to make in the past? Now is the time to consider them. It is also a superb time to identify even better changes for the future.

Get started – identify opportunities

Getting started with further change does not require major efforts or endless task force meetings. You can begin on your own.

First, do a “brain dump” of your observations and feelings about how the organization has performed thus far during the crisis. Here are some questions to help you get started:

- Has performance been excellent? In what ways yes, and what ways no?

- What was different from what you expected?

- How have the organization’s people reacted?

- How easy was it to adjust operations as needed?

- What ideas have come to your mind for improvement?

- Changes necessary for crisis survival have often exposed waste, inefficiency, and all manner of potential improvements. What are your opportunities?

Don’t edit yet (or at least wait until you get all the major thoughts out). Also, record any additional thoughts that come to mind as you focus on the questions.

Use the Business Success Model® to your advantage

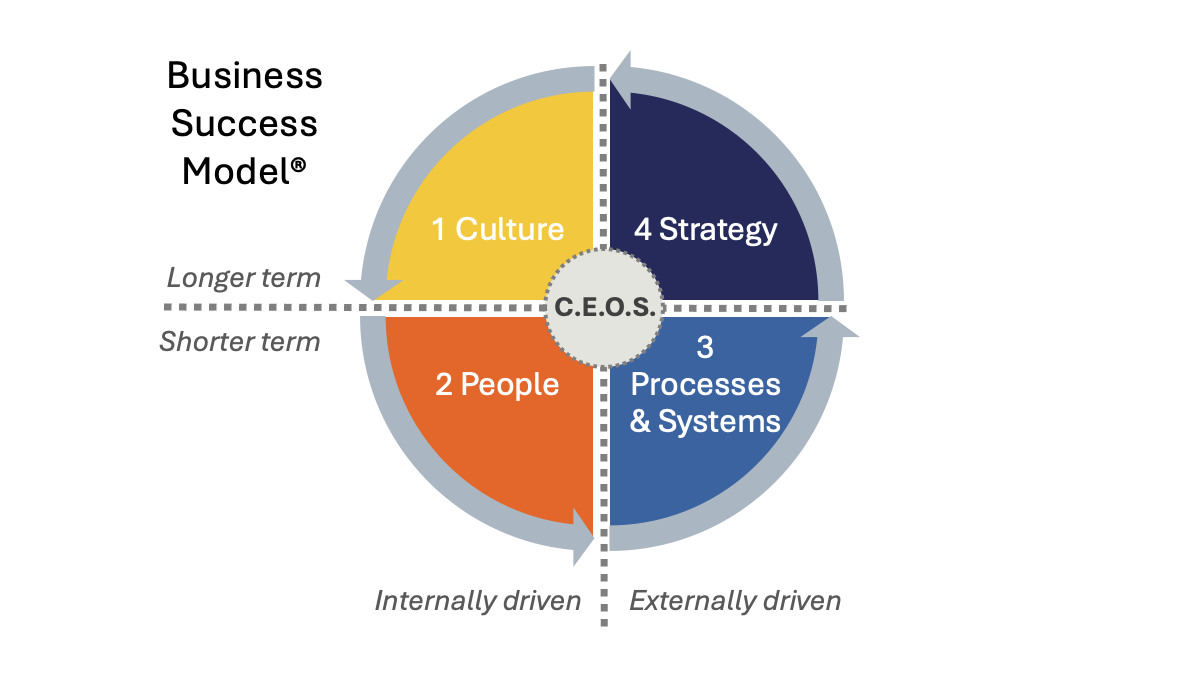

You’ve now captured a starting point for improvement. Let’s use some specific scenarios to add more options and fill in any gaps, using as a framework the Business Success Model® developed by Dr. Michael O’Connor.

Below are statements generally grouped by the four factors of the model. In each row is a pair of outcomes, representing different views of how your organization has performed in the current crisis. For each pair, decide which statement describes your situation best. Circle that statement. Note: for this exercise, if the situation is a mix of both descriptions, circle the left side. Only circle the right side if you strongly agree with the statement as characteristic of most, if not all, of your organization and all of the time.

| Culture |

|

|

| Our values were not a driving factor in how we reacted to and worked through the crisis. |

or |

We explicitly and consistently considered our organization’s values in all major decisions. Everyone clearly demonstrated the values in internal and external behavior. |

| Out of the four major stakeholder groups (customers, employees, owners/shareholders, significant others like our communities), we focused on results for one group, e.g., owner or shareholder value. Or Focus varied depending on the person and situation. |

or |

In our decisions and behavior, we explicitly and consistently considered how to achieve positive results for all of our major stakeholder groups. |

| We need to generate efficiencies, cut costs, and take other measures to survive, but there isn’t enough trust for people to be proactive or wholeheartedly embrace the need. People worry that efficiencies = layoffs. |

or |

We need to generate efficiencies, cut costs, and take other measures to survive, and there is enough trust, psychological safety, and real job safety so people proactively do so and wholeheartedly embrace the need. |

|

People |

||

| Our people were critical of efforts to keep operations going amid the crisis. It wasn’t “their problem,” and they exhibited scarcity and “entitlement” mindsets. |

or |

Our people consistently demonstrated high motivation, an abundance mindset, and commitment to our purpose and vision. |

| Our people were reactive and wanted to be told exactly what to do, how to do it, and when. |

or |

Our people consistently demonstrated initiative, high performance and adaptability. |

| Our leaders and managers did not serve us well. They had difficulty adapting to changing conditions. |

or |

Our leaders and managers superbly led by example and in adaptability. |

| (for those with a Board of Directors) Our Board made matters worse. |

or |

Our Board made us proud and supported the organization well. |

|

Processes & Systems |

||

| We wasted much time and effort because there were no clear priorities or people didn’t know what they were. |

or |

We were able to quickly prioritize what needed to be done and communicate clearly. There was little confusion or wasted effort. |

| We were unable to respond due to our core processes and systems or changing them proved to be very difficult and slow. |

or |

Our core business processes, practices, and systems that power our business model are strong, resilient, and easily adaptable. |

| Our support processes and systems did not support us or caused significant delays. |

or |

Our support business processes, practices, and systems (e.g., HR, finance, etc.) are strong, resilient, and easily adaptable. |

| Our people management structures (e.g., organization, work direction, coaching and development, performance evaluation, etc.) did not work “as is” during crisis or under remote work conditions or were even detrimental. |

or |

Our existing people management structures (e.g., organization, work direction, coaching and development, performance evaluation, etc.) functioned well. |

| Any lengthy illnesses or unplanned absences (or unfortunately, deaths in the worst case) of key people will radically affect our success. |

or |

We have succession plans and viable candidates ready if the need arises. |

| We don’t do improvement well, much less innovation, even in the best of times. Also, any changes are viewed with suspicion and fear of layoffs. |

or |

Improvement and innovation continued or even accelerated in the crisis, using our normal ways of working. |

|

Strategy |

||

| Our people did not know enough about how we function to understand what we needed to do and to adapt well on their own. |

or |

Everyone understands our business model sufficiently to understand what needs to be done and can operate independently as needed. |

| Our business model was difficult to change, if at all. |

or |

We quickly and easily adjusted our business model as needed. |

| No one wants to acknowledge the business model has problems or knows how to address them. We’re not sure if we can survive now or in the “new normal.” |

or |

We innovated rapidly to address business model shortfalls or take advantage of improvement opportunities. We continue to evaluate what the “new normal” will look like for us and take appropriate actions to thrive and prosper. |

If you have any trouble reading the table above, this is a link to the Business Model Success questions in PDF format.

If all of your circles were on the right, congratulations! Your past investments in agility have paid off now and will continue to do so in the future. Some additional questions for you:

- Can you apply your capabilities elsewhere in the market?

- Are there acquisition candidates that are much more attractive now because a significant number of their answers would be on the left?

- Can you gain market share against a competitor whose answers may be significantly on the left?

- Are there nonprofits in your community that could use your expertise?

If you had some circles on the left, don’t feel bad. You are not alone. Most organizations were designed for stability and not for accelerating rates of change. The good news is that now is an excellent time to make improvements.

For any circles on the left side, make a second pass. Star (and preferably rank order) the top three biggest impediments keeping the organization from the success it could achieve. You now have your candidate list for immediate improvements.

Pursue the opportunities

Now that you have your candidate list, evaluate those items in terms of the change equation. Clear identification of pain and gain must be a key factor in your organization’s internal communications and interactions. You must clearly express both the need for the change and why the pain of not making the change, or the benefits of the change, clearly outweigh the pain of going through the change. When you are done, people should be able to come to the same “obvious” conclusion as you did in terms of the change equation.

If the need for change will be obvious to all and you have reasonable data or proof of the need, don’t spend lots of time in lengthy change initiatives. Make explicit what’s on everyone’s minds and move forward. If the need isn’t clear or any items on your list are assumptions, take just enough action to validate that the need is real. It is data, not opinion, that demonstrates need and opportunity, and makes change far easier by gaining buy-in.

The larger the organization and the further away you are from day-to-day operations, the more you should validate that your views match the reality of the situation. Check your thinking with some trusted sources who are not “yes people.” If necessary, perform some studies or surveys to get “just enough” data and close any gaps in knowledge needed for decisions. Then move forward; don’t get stuck in “analysis paralysis.”

Then, follow the fundamentals of successful improvement projects and also the practice of communicating throughout the process, including celebration of “wins” as they come.

One last important point about communicating: In your case and especially in a crisis, lots of single point solutions and changes can confuse people and drain energy. They need to see the big picture and overall objective.

Therefore, keep casting your overall vision of the improvements and what it means to all stakeholders. Make sure that the specific changes fit in the vision and people can see how their improvements will support making the vision reality for themselves and other stakeholders. A positive view of the future will help people make it through difficulties in the present.

Prepare for the future!

In the days to come, keep focused on the key theme: don’t return to the past “normal” … leverage the current state of change to make a “new normal” that is dramatically better than the old! Continually communicate point as an underlying theme of your vision and the overall context for any items on your improvement list. This action will provide a positive message and hope amid the crisis and all the “negative noise” your people get daily from news and other sources.

Taking action on your improvements list can also dramatically improve your future ability to weather crises and take advantage of opportunities with speed and agility. Making the improvements will both take the organization to a higher level and enable it to stay there!

Accelerate improvement

Finally, make notes about how well this approach works in your situation. Also, consider how you can scale the approach to help others. Training and mentoring others achieves several benefits:

- You increase your leadership mastery … checking and adjusting your mindset and actions, as well as teaching others, identifies areas of understanding and skill that need improvement.

- It accelerates positive organizational change by broadening application through others.

- It can identify improvements to the process and questions themselves.

I’d love to hear how this helps you and if you have any improvement suggestions.

If you need any assistance or prefer to use our assessment services, we are ready to help.

By Mike Russell, author of Wrong Until Right – How to Succeed Despite Relentless Change

1 https://www.jimcollins.com/concepts/the-flywheel.html

Leave a Reply